Today, I’m going to share some knowledge and techniques on bruteforcing Windows passwords. Hopefully, some of you have thought about this and can give me even more advice. If you know anything, post it! Not too long ago, I wrote a Nmap script for bruteforcing Windows passwords over SMB. Then, even more recently, I re-wrote it. Over these two editions, and with a whole lot of research about SMB in the past six months or so, I’ve learned a lot of cool stuff.

Not only will you get some great advice, I’m also going to show you an example of what NOT to do, based on an actual attack against my network! Not too bad for a blog, eh?

Disclaimer: All these techniques, except where noted, were invented by me. They may very well be used in other projects, and I’m almost certain the obvious ones are.

Oh, and in case you don’t know what bruteforcing is, it’s a technique where the attacker guesses username/password combinations to gain access to a server.

Tip 1: Don't kill your connections

Let’s start with something easy, shall we? This one is pretty obvious, but it’s worth mentioning. If you’ve read my other blog posts, which I’m sure you have, you’ll know that the first three messages sent in SMB are: SMB_COM_NEGOTIATE SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX SMB_COM_TREE_CONNECT_ANDX

And the last two are: SMB_COM_TREE_DISCONNECT SMB_COM_LOGOFF_ANDX

The magic happens in SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX. That’s where the username and password are sent. If the username and password are wrong, what do you do? Hangup and call back? Nope! All you have to do is send SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX again. No fussing with new TCP sessions and all the extra overhead!

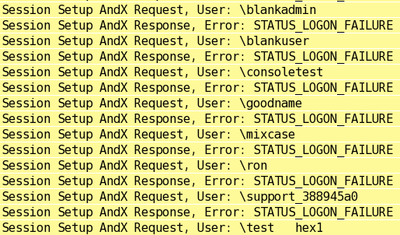

Here’s a picture (you heard that right, a picture!) of that happening:

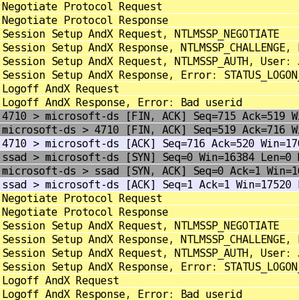

Compare that to another unnamed bruteforce program (mostly unnamed because this is one that somebody ran against me last night (I expect it was malware of some kind), which does this:

That’s only TWO attempts! On my attack, in less space, I tried EIGHT. Something else worth pointing out is the second screenshot shows extended security negotiations, which is why you see two Session Setup requests per attempt. And that brings us to…

Tip 2: Stick with the basics

This is simple and obvious, much like Tip 1, but it’s important. Take another look at the screenshots in Tip 1; notice that each login request in mine is 2 packets, compared to 4 packets in theirs (not counting the other network nonsense). Since all these login packets are roughly the same size, that means mine uses half the network traffic. On a slower network or for a long test, that could be significant.

The reason for the extra traffic is that Windows defaults to using extended security negotiations, or NTLMSSP. NTLMSSP is more modern, and is probably the “proper” way of connecting to Windows. However, all versions of Windows, at least up to Vista, still understand the old style, so why not take advantage? My Nmap libraries also default to NTLMSSP, but scripts (like smb-brute) can opt out. The issue here is that, if you’re trying to use Windows’ libraries, you can’t get this level of control (nor can you do the tricks from Tips 1, 3, 4, and maybe others) .

So, what’s a programmer to do? In this case, the only option is to re-implement SMB. Don’t look at me like that! I realize that implementing the whole SMB protocol is a daunting task, but keep in mind that you only need the first two packets, and the first one is static. Not so bad, eh?

Tip 3: Who has accounts here? (part 1)

This is probably the most confusing tip, but is also one of the most important ones. I’ll do my best to explain it clearly, and to show some examples. Oh, and don’t blame me for making this confusing, blame Microsoft – Windows logins are funny, and this funniness is both a curse and a blessing.

When you log into Windows, what happens when you enter an invalid username? What about an invalid password? Just access denied, right? And what if you enter the correct username and correct password? Access granted? If you answered “yes” to any of the above, you’re wrong. If you answered “no”, you’re also wrong. The answer is, “it depends”.

Windows’ normal behaviour, for some definition of normal, is to deny access to invalid usernames and passwords. This is my Nmap debug output, from a Windows 2003 machine with the guest account disabled:

smb-brute: Server's response to invalid usernames: FAIL smb-brute: Server's response to invalid passwords: FAIL

So the login failed on both attempts. Awesome, right?

Here’s the same scan, except that the guest account is enabled:

smb-brute: Server's response to invalid usernames: GUEST_ACCESS smb-brute: Server's response to invalid passwords: FAIL

What’s going on here? Well, when the guest account is enabled, and you type an invalid username (and, obviously, invalid password), you’re logged in as guest. If you type a valid username with an invalid password, it fails. This may appear annoying, and it is, but it’s more often a blessing in disguise. Why? Well, here’s the next piece of my output:

smb-brute: Invalid username and password response are different, so identifying valid accounts is possible smb-brute: Checking which account names exist (based on what goes to the 'guest' account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'root' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'admin' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'administrator' => 'FAIL' (may be valid) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'webadmin' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'sysadmin' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'netadmin' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'guest' => 'SUCCESS' (likely valid) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'user' -> 'GUEST_ACCESS' (invalid account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'web' => 'FAIL' (may be valid) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'test' => 'FAIL' (may be valid)

Because Windows is telling us something different for invalid usernames compared to invalid passwords, we can weed out which accounts actually exist! So, in that example, the ‘web’, ‘test’, and ‘administrator’ users returned FAIL. Since we already know that invalid usernames grant us GUEST_ACCESS, and invalid passwords return FAIL, we can deduce that those three accounts exist while the rest (except, of course, for ‘guest’) don’t. Suddenly, the 10 usernames in our dictionary become three, and the whole bruteforce is going to take 30% of the original time.

For completeness, I’d better say that this isn’t the only trick when dealing with Windows. Windows XP, for example, defaults to giving guest access to every account, no matter which password is entered. Bruteforcing will completely fail in that case, but at least we always get guest access! Another little trick is that if the ‘guest’ account is in another state (expired, locked out, etc), all invalid usernames will show that status. So, if guest is locked out, invalid usernames will return LOCKED_OUT instead of GUEST_ACCESS.

Tip 4: Case? Who needs case?

This is another very cool and useful idea trick. The idea was given to me by Brandon on the Nmap team, and filled in by Rainbow Crack. Then I improved the idea to work better with network applications. At least, I think I did (I haven’t checked how Rainbow Crack does this).

As you know from reading my blogs, there are two (main) types of Windows login hashes: Lanman and NTLM. Lanman is weak, boring, and case insensitive. NTLM is strong, boring, and case sensitive. When logging into Windows, you can use one, the other, or both, Windows doesn’t care.

Disclaimer: Vista no longer stores Lanman, so Vista cares.

Taking advantage of case sensitivity, smb-brute will start by using pure Lanman (unless it detects Vista or is overridden by the user). Once it finds a password, it flips to NTLM, where it tries the password again. If it fails, then the password has uppercase characters in it. The script will then switch over to case discovery, where it’ll try every combination of upper and lowercase until it finds the proper NTLM password. This takes 2length tries, at the worst case. So, a 14-character password will take 214 or 16,384 guesses at the worst case. That’s pretty bad, but not terrible. There are, however, a few mitigating factors. The first one, of course, is that nobody with a 14-character password is going to be using a dictionary password, so we won’t be finding it anyways. More than likely, the longest password you’ll crack is an 8-character password, which is 28 or 256 checks at the worst case. Much better!

Up to here, this idea is straight from Rainbow Crack. This is where I add a twist to it. Rainbow Crack has the advantage of running locally on the system, so 16,000 checks isn’t actually unreasonable. smb-brute, however, has to run on the network, making efficiency important. Well, let’s figure out how people most commonly use case in their passwords, shall we? From the passwords stolen from MySpace a couple years back, here are a few quick statistics (disclaimer: these are for phished passwords that contain only letters): 4918 – All lowercase 1623 – All uppercase 59 – One uppercase 6 – Two uppercase 7 – Three uppercase 1 – Four uppercase 1 – Five uppercase 0 – Six uppercase 0 – Seven uppercase etc.

Obviously, the statistics for >1 uppercase exclude strings that are entirely uppercase.

From these statistics, the trend is pretty obvious (and, interestingly, this is exactly the trend I predicted and implemented before I ever looked at statistics :) ) – most people use all lower, all upper, or a minimal number of uppercase characters. Another assumption that I haven’t actually tested yet is that the uppercase characters tend to be closer to the front of the string, because a lot of people capitalize the first letter. So, with this in mind, I implemented an algorithm that generates a list of passwords in that order. For example, the password “test” would have the following permutations, in this order: test TEST Test tEst teSt tesT TEst TeSt TesT tESt tEsT teST TESt TEsT TeST tEST

I wrote this by converting the case representation (upper/lower) to binary (1/0) (for example, ‘1000’ represents ‘Test’ and ‘1011’ represents ‘TeST’). Then, all possible binary numbers between 0 and 2strlen - 1 are sorted by the number of ones they contain. So, the strings with a single capital (one ‘1’) ended up at the top, and the strings with all caps (four ‘1’s) ended up at the bottom, like this: 0000 1000 0100 0010 0001 1100 1010 1001 0110 0101 0011 1110 1101 1011 0111 1111

After the ‘1111’ is moved to second place (all caps is special and breaks the pattern), these are converted back to letters, and the passwords are tested.

smb-brute: Determining password's case (mixcase:butterfly1) smb-brute: Result: mixcase:BuTTeRfLY1

Tip 5: Who has accounts here? (part 2)

Hopefully by now, we’ve trimmed down the list of accounts to valid ones, then found the passwords of a couple of those. The problem is, on my machines, I have weird usernames. What are the odds that “test7”, “consoletest”, and “mixcase” are going to be in your bruteforce list? Pretty small.

But, there’s hope! If you have a fully blown SMB implementation with MSRPC, as soon as you have a guest (or, better, user) password, you can start enumerating users. If you’ve been keeping up with my scripts, you’ll know that smb-enum-users.nse does exactly that. So, borrowing a few tricks from that script, as soon as smb-brute.nse is able, it performs a user enumeration. On Windows 2000, or Windows XP and higher with ‘guest’ enabled, it will get the list of users immediately. If guest is disabled on Windows XP or higher system, it won’t get the list until it finds an actual account.

Once we have a proper username list, the possibility of success increases dramatically, especially if the server has a significant number of user accounts.

Here is some output to demonstrate:

smb-brute: Couldn't enumerate users (normal for Windows XP and higher), using unpwdb initially [...] smb-brute: Determining password's case (test:password1) smb-brute: Result: test:password1 SMB: Extended login as \test succeeded SMB: Saved an aministrative account: test smb-brute: Trying to get user list from server using newly discovered account SMB: Login as \test succeeded smb-brute: Found 19 accounts to check! smb-brute: Checking which account names exist (based on what goes to the 'guest' account) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'administrator' => 'FAIL' (may be valid) smb-brute: Invalid password for 'allupper' => 'FAIL' (may be valid) [...]

Tip 6: Passwords first, users can wait

This is a great idea, proposed by Brandon. My original script looped through each username, then each password for that user. Since most of my password dictionaries are sorted by frequency of use, the first username would be paired with every password, from the most common to the least common. Then the next username would be paired the same way, and so on. With a large password dictionary, each user would take a long time.

Brandon’s idea was to start with a password, and try every possible user for it. That means that the most common password (say, ‘password1’), will be tried for every account before the next password (say, ‘abc123’) is tried.

This is great, and will find common passwords much faster. But what are the disadvantages?

Well, the biggest disadvantage I ran across is that, if the server enforces account lockouts, then all accounts will be brought to within one guess from being locked out. That can cause a DoS on a server pretty fast, especially if the script is run a second time. That bring us to…

Tip 7: The canary warned us!

Let’s say there are three users, “ron”, “jim”, and “mary”, and the system locks people out at 3 failed logins. The test will look like this: ron:(random garbage) => fail jim:(random garbage) => fail mary:(random garbage) => fail ron:abc123 => fail jim:abc123 => fail mary:abc123 => fail ron:iloveyou => fail (+ locked out) (quit)

The reason for the initial random password is to check whether or not the account exists and, if it exists, whether or not it’s locked out or disabled. If the script is run a second time, in the phase that checks for accounts’ existence, every account will be locked. For a pen-tester, that isn’t ideal. And if the server’s being actively used, that’s also bad because a user might mistype their password once (I pretty much always do) before logging in.

To mitigate this issue, I came up with what I consider to be a clever trick. Remember, though, that just because I think it’s clever, doesn’t make it clever. Anyway, at the beginning of the scan, the first valid-looking account found has a number of random passwords attempted. I call the account the canary, after the traditional (and horrible ;) ) practice of bringing a canary with miners to see if it dies. By default, three probes are sent, but it’s configurable with commandline arguments. If the account is locked on the first three probes, the scan ends right away. That’s easy. But let’s say the lockout threshold has been set to six? This is what’ll happen: ron:(random garbage) => fail [testing initial state] jim:(random garbage) => fail [testing initial state] mary:(random garbage) => fail [testing initial state] ron:(random garbage) => fail [canary] ron:(random garbage) => fail [canary] ron:(random garbage) => fail [canary] ron:password1 => fail jim:password1 => fail mary:password1 => fail ron:abc123 => fail (+ locked out)

The canary is locked out, but the counters for the other accounts are still 2 – well below the lockout threshold. One account is still locked out, but that’s far better than every account being locked out.

Tip 8: What's your access level?

That brings us to our final tip: how to determine access level?

smb-brute.nse saves its credentials, but how do we know which credentials to save? What if we save the guest account when a bunch of administrator accounts were discovered?

I wrestled with this problem for a little while, since I didn’t know of any way to get a user’s groups remotely. It wouldn’t surprise me if there was a LSA function to do it, but I didn’t dig that deep. Instead, I originally checked if username == “Administrator” then keep, and if username == “Guest” then reject. Not an ideal solution, and I wanted something better.

That’s when I realized, a simple way to tell them apart is to do something that only one can do! In my current version of smb.lua, when a user tries to save a name, it tries to get the server’s statistics (the same way as smb-server-stats.nse). If it succeeds, it’s administrator; otherwise, it’s user or lower. This technique works great against all Windows up to (not including) Vista. Here is an example run, where ‘test’ is an Administrator and Windows 2003 is the target:

smb-brute: Detecting server lockout on 'allupper' with 3 canaries smb-brute: Determining password's case (blankadmin:) smb-brute: Result: blankadmin: smb-brute: Determining password's case (blankuser: ) smb-brute: Result: blankuser: smb-brute: Determining password's case (guest: ) smb-brute: Result: guest: smb-brute: Determining password's case (test:password1) smb-brute: Result: test:password1 SMB: Extended login as \test succeeded SMB: Saved an aministrative account: test ... </pre> In my next version, I plan to look into other functions that require administrative privileges to run; one promising function is GetShareInfo() (the function that retrieves information about a share, such as the path). I believe it'll work better than GetServerStats(). Conclusion

As I said, while taking pokes at SMB authentication, I discovered a lot of cool tricks. I listed all eight things I considered significant and used to my advantage. Hopefully they either come in handy to somebody or, more likely, hopefully you found this interesting! If you made it all the way to the end, you must think it's something. :)

Comments

Join the conversation on this Mastodon post (replies will appear below)!

Loading comments...